MR Sunny Faridi Chairman Jasfar Founder Aiqcsr

MR Sunny Faridi Chairman Jasfar Founder Aiqcsr

QUANTUM

Quantum Introductions

- A quantum computer is a computer that exploits quantum mechanical phenomena. At small scales, physical matter exhibits properties of both particles and waves, and quantum computing leverages this behavior using specialized hardware. Classical physics cannot explain the operation of these quantum devices, and a scalable quantum computer c

- A quantum computer is a computer that exploits quantum mechanical phenomena. At small scales, physical matter exhibits properties of both particles and waves, and quantum computing leverages this behavior using specialized hardware. Classical physics cannot explain the operation of these quantum devices, and a scalable quantum computer could perform some calculations exponentially faster than any modern "classical" computer. In particular, a large-scale quantum computer could break widely used encryption schemes and aid physicists in performing physical simulations; however, the current state of the art is largely experimental and impractical.

- The basic unit of information in quantum computing is the qubit, similar to the bit in traditional digital electronics. Unlike a classical bit, a qubit can exist in a superposition of its two "basis" states, which loosely means that it is in both states simultaneously. When measuring a qubit, the result is a probabilistic output of a classical bit. If a quantum computer manipulates the qubit in a particular way, wave interference effects can amplify the desired measurement results. The design of quantum algorithms involves creating procedures that allow a quantum computer to perform calculations efficiently and quickly.

- Physically engineering high-quality qubits has proven challenging. If a physical qubit is not sufficiently isolated from its environment, it suffers from quantum decoherence, introducing noise into calculations. National governments have invested heavily in experimental research that aims to develop scalable qubits with longer coherence times and lower error rates. Two of the most promising technologies are superconductors (which isolate an electrical current by eliminating electrical resistance) and ion traps (which confine a single atomic particle using electromagnetic fields).

- Any computational problem that can be solved by a classical computer can also be solved by a quantum computer.[2] Conversely, any problem that can be solved by a quantum computer can also be solved by a classical computer, at least in principle given enough time. In other words, quantum computers obey the Church–Turing thesis. This means that while quantum computers provide no additional advantages over classical computers in terms of computability, quantum algorithms for certain problems have significantly lower time complexities than corresponding known classical algorithms. Notably, quantum computers are believed to be able to solve many problems quickly that no classical computer could solve in any feasible amount of time—a feat known as "quantum supremacy." The study of the computational complexity of problems with respect to quantum computers is known as quantum complexity theory.

- History[edit]

- For a chronological guide, see Timeline of quantum computing and communication.

The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference.

The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference. - For many years, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science formed distinct academic communities.[3] Modern quantum theory developed in the 1920s to explain the wave–particle duality observed at atomic scales,[4] and digital computers emerged in the following decades to replace human computers for tedious calculations.[5] Both disciplines had practical applications during World War II; computers played a major role in wartime cryptography,[6] and quantum physics was essential for the nuclear physics used in the Manhattan Project.[7]

- As physicists applied quantum mechanical models to computational problems and swapped digital bits for qubits, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science began to converge. In 1980, Paul Benioff introduced the quantum Turing machine, which uses quantum theory to describe a simplified computer.[8] When digital computers became faster, physicists faced an exponential increase in overhead when simulating quantum dynamics,[9] prompting Yuri Manin and Richard Feynman to independently suggest that hardware based on quantum phenomena might be more efficient for computer simulation.[10][11][12] In a 1984 paper, Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard applied quantum theory to cryptography protocols and demonstrated that quantum key distribution could enhance information security.[13][14]

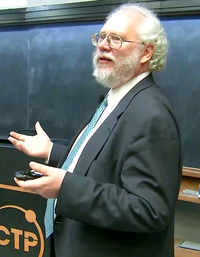

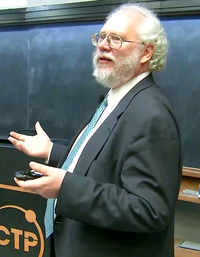

Peter Shor (pictured here in 2017) showed in 1994 that a scalable quantum computer would be able to break RSA encryption.

Peter Shor (pictured here in 2017) showed in 1994 that a scalable quantum computer would be able to break RSA encryption.- Quantum algorithms then emerged for solving oracle problems, such as Deutsch's algorithm in 1985,[15] the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm in 1993,[16] and Simon's algorithm in 1994.[17] These algorithms did not solve practical problems, but demonstrated mathematically that one could gain more information by querying a black box with a quantum state in superposition, sometimes referred to as quantum parallelism.[18] Peter Shor built on these results with his 1994 algorithms for breaking the widely used RSA and Diffie–Hellman encryption protocols,[19] which drew significant attention to the field of quantum computing.[20] In 1996, Grover's algorithm established a quantum speedup for the widely applicable unstructured search problem.[21][22] The same year, Seth Lloyd proved that quantum computers could simulate quantum systems without the exponential overhead present in classical simulations,[23] validating Feynman's 1982 conjecture.[24]

- Over the years, experimentalists have constructed small-scale quantum computers using trapped ions and superconductors.[25] In 1998, a two-qubit quantum computer demonstrated the feasibility of the technology,[26][27] and subsequent experiments have increased the number of qubits and reduced error rates.[25] In 2019, Google AI and NASA announced that they had achieved quantum supremacy with a 54-qubit machine, performing a computation that is impossible for any classical computer.[28][29][30] However, the validity of this claim is still being actively researched.[31][32]

- The threshold theorem shows how increasing the number of qubits can mitigate errors,[33] yet fully fault-tolerant quantum computing remains "a rather distant dream".[34] According to some researchers, noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) machines may have specialized uses in the near future, but noise in quantum gates limits their reliability.[34]

- Investment in quantum computing research has increased in the public and private sectors.[35][36] As one consulting firm summarized,[37]

- ... investment dollars are pouring in, and quantum-computing start-ups are proliferating. ... While quantum computing promises to help businesses solve problems that are beyond the reach and speed of conventional high-performance computers, use cases are largely experimental and hypothetical at this early stage.

- Quantum information processing[edit]

- See also: Introduction to quantum mechanics

- Computer engineers typically describe a modern computer's operation in terms of classical electrodynamics. Within these "classical" computers, some components (such as semiconductors and random number generators) may rely on quantum behavior, but these components are not isolated from their environment, so any quantum information quickly decoheres. While programmers may depend on probability theory when designing a randomized algorithm, quantum mechanical notions like superposition and interference are largely irrelevant for program analysis.

- Quantum programs, in contrast, rely on precise control of coherent quantum systems. Physicists describe these systems mathematically using linear algebra. Complex numbers model probability amplitudes, vectors model quantum states, and matrices model the operations that can be performed on these states. Programming a quantum computer is then a matter of composing operations in such a way that the resulting program computes a useful result in theory and is implementable in practice.

- The prevailing model of quantum computation describes the computation in terms of a network of quantum logic gates.[38] This model is a complex linear-algebraic generalization of boolean circuits.[a]

- Quantum information[edit]

- The qubit serves as the basic unit of quantum information. It represents a two-state system, just like a classical bit, except that it can exist in a superposition of its two states. In one sense, a superposition is like a probability distribution over the two values. However, a quantum computation can be influenced by both values at once, inexplicable by either state individually. In this sense, a "superposed" qubit stores both values simultaneously.

- A two-dimensional vector mathematically represents a qubit state. Physicists typically use Dirac notation for quantum mechanical linear algebra, writing |ψ⟩ 'ket psi' for a vector labeled ψ. Because a qubit is a two-state system, any qubit state takes the form α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where |0⟩ and |1⟩ are the standard basis states,[b] and α and β are the probability amplitudes. If either α or β is zero, the qubit is effectively a classical bit; when both are nonzero, the qubit is in superposition. Such a quantum state vector acts similarly to a (classical) probability vector, with one key difference: unlike probabilities, probability amplitudes are not necessarily positive numbers. Negative amplitudes allow for destructive wave interference.[c]

- When a qubit is measured in the standard basis, the result is a classical bit. The Born rule describes the norm-squared correspondence between amplitudes and probabilities—when measuring a qubit α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, the state collapses to |0⟩ with probability |α|2, or to |1⟩ with probability |β|2. Any valid qubit state has coefficients α and β such that |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. As an example, measuring the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩ would produce either |0⟩ or |1⟩ with equal probability.

- Each additional qubit doubles the dimension of the state space. As an example, the vector 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|01⟩ represents a two-qubit state, a tensor product of the qubit |0⟩ with the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩. This vector inhabits a four-dimensional vector space spanned by the basis vectors |00⟩, |01⟩, |10⟩, and |11⟩. The Bell state 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|11⟩ is impossible to decompose into the tensor product of two individual qubits—the two qubits are entangled because their probability amplitudes are correlated. In general, the vector space for an n-qubit system is 2n-dimensional, and this makes it challenging for a classical computer to simulate a quantum one: representing a 100-qubit system requires storing 2100 classical values.

- Unitary operators[edit]

- See also: Unitarity (physics)

- The state of this one-qubit quantum memory can be manipulated by applying quantum logic gates, analogous to how classical memory can be manipulated with classical logic gates. One important gate for both classical and quantum computation is the NOT gate, which can be represented by a matrix

- �:=(0110).

Mathematically, the application of such a logic gate to a quantum state vector is modelled with matrix multiplication. Thus

- �|0⟩=|1⟩

and �|1⟩=|0⟩

.

- The mathematics of single qubit gates can be extended to operate on multi-qubit quantum memories in two important ways. One way is simply to select a qubit and apply that gate to the target qubit while leaving the remainder of the memory unaffected. Another way is to apply the gate to its target only if another part of the memory is in a desired state. These two choices can be illustrated using another example. The possible states of a two-qubit quantum memory are

- |00⟩:=(1000);|01⟩:=(0100);|10⟩:=(0010);|11⟩:=(0001).

The CNOT gate can then be represented using the following matrix:CNOT:=(1000010000010010).

As a mathematical consequence of this definition, CNOT|00⟩=|00⟩

, CNOT|01⟩=|01⟩

, CNOT|10⟩=|11⟩

, and CNOT|11⟩=|10⟩

. In other words, the CNOT applies a NOT gate (�

from before) to the second qubit if and only if the first qubit is in the state |1⟩

. If the first qubit is |0⟩

, nothing is done to either qubit.

- In summary, a quantum computation can be described as a network of quantum logic gates and measurements. However, any measurement can be deferred to the end of quantum computation, though this deferment may come at a computational cost, so most quantum circuits depict a network consisting only of quantum logic gates and no measurements.

- Quantum parallelism[edit]

- Quantum parallelism refers to the ability of quantum computers to evaluate a function for multiple input values simultaneously. This can be achieved by preparing a quantum system in a superposition of input states, and applying a unitary transformation that encodes the function to be evaluated. The resulting state encodes the function's output values for all input values in the superposition, allowing for the computation of multiple outputs simultaneously. This property is key to the speedup of many quantum algorithms.[18]

- Quantum programming [edit]

- Further information: Quantum programming

- There are a number of models of computation for quantum computing, distinguished by the basic elements in which the computation is decomposed.

- Gate array [edit]

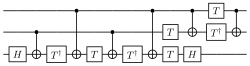

A quantum circuit diagram implementing a Toffoli gate from more primitive gates

A quantum circuit diagram implementing a Toffoli gate from more primitive gates- A quantum gate array decomposes computation into a sequence of few-qubit quantum gates. A quantum computation can be described as a network of quantum logic gates and measurements. However, any measurement can be deferred to the end of quantum computation, though this deferment may come at a computational cost, so most quantum circuits depict a network consisting only of quantum logic gates and no measurements.

- Any quantum computation (which is, in the above formalism, any unitary matrix of size 2�×2�

over �

qubits) can be represented as a network of quantum logic gates from a fairly small family of gates. A choice of gate family that enables this construction is known as a universal gate set, since a computer that can run such circuits is a universal quantum computer. One common such set includes all single-qubit gates as well as the CNOT gate from above. This means any quantum computation can be performed by executing a sequence of single-qubit gates together with CNOT gates. Though this gate set is infinite, it can be replaced with a finite gate set by appealing to the Solovay-Kitaev theorem.

- Measurement-based quantum computing[edit]

- A measurement-based quantum computer decomposes computation into a sequence of Bell state measurements and single-qubit quantum gates applied to a highly entangled initial state (a cluster state), using a technique called quantum gate teleportation.

- Adiabatic quantum computing[edit]

- An adiabatic quantum computer, based on quantum annealing, decomposes computation into a slow continuous transformation of an initial Hamiltonian into a final Hamiltonian, whose ground states contain the solution.[41]

- Topological quantum computing[edit]

- A topological quantum computer decomposes computation into the braiding of anyons in a 2D lattice.[42]

- Quantum Turing machine[edit]

- A quantum Turing machine is the quantum analog of a Turing machine.[8] All of these models of computation—quantum circuits,[43] one-way quantum computation,[44] adiabatic quantum computation,[45] and topological quantum computation[46]—have been shown to be equivalent to the quantum Turing machine; given a perfect implementation of one such quantum computer, it can simulate all the others with no more than polynomial overhead. This equivalence need not hold for practical quantum computers, since the overhead of simulation may be too large to be practical.

How It Work

The basic unit of information in quantum computing is the qubit, similar to the bit in traditional digital electronics. Unlike a classical bit, a qubit can exist in a superposition of its two "basis" states, which loosely means that it is in both states simultaneously. When measuring a qubit, the result is a probabilistic output of a cla

The basic unit of information in quantum computing is the qubit, similar to the bit in traditional digital electronics. Unlike a classical bit, a qubit can exist in a superposition of its two "basis" states, which loosely means that it is in both states simultaneously. When measuring a qubit, the result is a probabilistic output of a classical bit. If a quantum computer manipulates the qubit in a particular way, wave interference effects can amplify the desired measurement results. The design of quantum algorithms involves creating procedures that allow a quantum computer to perform calculations efficiently and quickly.

Physically engineering high-quality qubits has proven challenging. If a physical qubit is not sufficiently isolated from its environment, it suffers from quantum decoherence, introducing noise into calculations. National governments have invested heavily in experimental research that aims to develop scalable qubits with longer coherence times and lower error rates. Two of the most promising technologies are superconductors (which isolate an electrical current by eliminating electrical resistance) and ion traps (which confine a single atomic particle using electromagnetic fields).

Any computational problem that can be solved by a classical computer can also be solved by a quantum computer.[2] Conversely, any problem that can be solved by a quantum computer can also be solved by a classical computer, at least in principle given enough time. In other words, quantum computers obey the Church–Turing thesis. This means that while quantum computers provide no additional advantages over classical computers in terms of computability, quantum algorithms for certain problems have significantly lower time complexities than corresponding known classical algorithms. Notably, quantum computers are believed to be able to solve many problems quickly that no classical computer could solve in any feasible amount of time—a feat known as "quantum supremacy." The study of the computational complexity of problems with respect to quantum computers is known as quantum complexity theory.

History[edit]

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of quantum computing and communication. The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference.

The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference.

For many years, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science formed distinct academic communities.[3] Modern quantum theory developed in the 1920s to explain the wave–particle duality observed at atomic scales,[4] and digital computers emerged in the following decades to replace human computers for tedious calculations.[5] Both diy that one could gain more information by querying a black box with a quantum state in superposition, sometimes referred to as quantum parallelism.[18] Peter Shor built on these results with his 1994 algorithms for breaking the widely used RSA and Diffie–Hellman encryption protocols,[19] which drew significant attention to the field of quantum computing.[20] In 1996, Grover's algorithm established a quantum speedup for the widely applicable unstructured search problem.[21][22] The same year, Seth Lloyd proved that quantum computers could simulate quantum systems without the exponential overhead present in classical simulations,[23] validating Feynman's 1982 conjecture.[24]

Over the years, experimentalists have constructed small-scale quantum computers using trapped ions and superconductors.[25] In 1998, a two-qubit quantum computer demonstrated the feasibility of the technology,[26][27] and subsequent experiments have increased the number of qubits and reduced error rates.[25] In 2019, Google AI and NASA announced that they had achieved quantum supremacy with a 54-qubit machine, performing a computation that is impossible for any classical computer.[28][29][30] However, the validity of this claim is still being actively researched.[31][32]

The threshold theorem shows how increasing the number of qubits can mitigate errors,[33] yet fully fault-tolerant quantum computing remains "a rather distant dream".[34] According to some researchers, noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) machines may have specialized uses in the near future, but noise in quantum gates limits their reliability.[34]

Investment in quantum computing research has increased in the public and private sectors.[35][36] As one consulting firm summarized,[37]

... investment dollars are pouring in, and quantum-computing start-ups are proliferating. ... While quantum computing promises to help businesses solve problems that are beyond the reach and speed of conventional high-performance computers, use cases are largely experimental and hypothetical at this early stage.

Quantum information processing[edit]

See also: Introduction to quantum mechanics

Computer engineers typically describe a modern computer's operation in terms of classical electrodynamics. Within these "classical" computers, some components (such as semiconductors and random number generators) may rely on quantum behavior, but these components are not isolated from their environment, so any quantum information quickly decoheres. While programmers may depend on probability theory when designing a randomized algorithm, quantum mechanical notions like superposition and interference are largely irrelevant for program analysis.

Quantum programs, in contrasdividually. In this sense, a "superposed" qubit stores both values simultaneously.

A two-dimensional vector mathematically represents a qubit state. Physicists typically use Dirac notation for quantum mechanical linear algebra, writing |ψ⟩ 'ket psi' for a vector labeled ψ. Because a qubit is a two-state system, any qubit state takes the form α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where |0⟩ and |1⟩ are the standard basis states,[b] and α and β are the probability amplitudes. If either α or β is zero, the qubit is effectively a classical bit; when both are nonzero, the qubit is in superposition. Such a quantum state vector acts similarly to a (classical) probability vector, with one key difference: unlike probabilities, probability amplitudes are not necessarily positive numbers. Negative amplitudes allow for destructive wave interference.[c]

When a qubit is measured in the standard basis, the result is a classical bit. The Born rule describes the norm-squared correspondence between amplitudes and probabilities—when measuring a qubit α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, the state collapses to |0⟩ with probability |α|2, or to |1⟩ with probability |β|2. Any valid qubit state has coefficients α and β such that |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. As an example, measuring the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩ would prtheir probability amplitudes are correlated. In general, the vector space for an n-qubit system is 2n-dimensional, and this makes it challenging for a classical computer to simulate a quantum one: representing a 100-qubit system requires storing 2100 classical values.

Unitary operators[edit]

See also: Unitarity (physics)

The state of this one-qubit quantum memory can be manipulated by applying quantum logic gates, analogous to how classical memory can be manipulated with classical logic gates. One important gate for both classical and quantum computation is the NOT gate, which can be represented by a matrix

�:=(0110).

�|0⟩=|1⟩

The mathematics of single qubit gates can be extended to operate on multi-qubit quantum memories in two important ways. One way is simply to select a qubit and apply that gate to the target qubit while leaving the remainder of the memory unaffected. Another way is to apply the gate to its target only if another part of the memory is in a desired state. These two choices can be illustrated using another example. The possible states of a two-qubit quantum memory are

|00⟩:=(1000);|01⟩:=(0100);|10⟩:=(0010);|11⟩:=(0001).

Quantum parallelism[edit]

Quantum parallelism refers to the ability of quantum computers to evaluate a function for multiple input values simultaneously. This can be achieved by preparing a quantum system in a superposition of input states, and applying a unitary transformation that encodes the function to be evaluated. The resulting state encodes the function's output values for all input values in the superposition, allowing for the computation of multiple outputs simultaneously. This property is key to the speedup of many quantum algorithms.[18]

Quantum programming [edit]

Further information: Quantum programming

There are a number of models of computation for quantum computing, distinguished by the basic elements in which the computatily that enables this construction is known as a universal gate set, since a computer that can run such circuits is a universal quantum computer. One common such set includes all single-qubit gates as well as the CNOT gate from above. This means any quantum computation can be performed by executing a sequence of single-qubit gates together with CNOT gates. Though this gate set is infinite, it can be replaced with a finite gate set by appealing to the Solovay-Kitaev theorem.

Measurement-based quantum computing[edit]

A measurement-based quantum computer decomposes computatimay be too large to be practical.

Our Mission

Our Mission

Physically engineering high-quality qubits has proven challenging. If a physical qubit is not sufficiently isolated from its environment, it suffers from quantum decoherence, introducing noise into calculations. National governments have invested heavily in experimental research that aims to develop scalable qubits with longer coherence t

Physically engineering high-quality qubits has proven challenging. If a physical qubit is not sufficiently isolated from its environment, it suffers from quantum decoherence, introducing noise into calculations. National governments have invested heavily in experimental research that aims to develop scalable qubits with longer coherence times and lower error rates. Two of the most promising technologies are superconductors (which isolate an electrical current by eliminating electrical resistance) and ion traps (which confine a single atomic particle using electromagnetic fields).

Any computational problem that can be solved by a classical computer can also be solved by a quantum computer.[2] Conversely, any problem that can be solved by a quantum computer can also be solved by a classical computer, at least in principle given enough time. In other words, quantum computers obey the Church–Turing thesis. This means that while quantum computers provide no additional advantages over classical computers in terms of computability, quantum algorithms for certain problems have significantly lower time complexities than corresponding known classical algorithms. Notably, quantum computers are believed to be able to solve many problems quickly that no classical computer could solve in any feasible amount of time—a feat known as "quantum supremacy." The study of the computational complexity of problems with respect to quantum computers is known as quantum complexity theory.

History[edit]

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of quantum computing and communication. The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference.

The Mach–Zehnder interferometer shows that photons can exhibit wave-like interference.

For many years, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science formed distinct academic communities.[3] Modern quantum theory developed in the 1920s to explain the wave–particle duality observed at atomic scales,[4] and digital computers emerged in the following decades to replace human computers for tedious calculations.[5] Both disciplines had practical applications during World War II; computers played a major role in wartime cryptography,[6] and quantum physics was essential for the nuclear physics used in the Manhattan Project.[7]

As physicists applied quantum mechanical models to computational problems and swapped digital bits for qubits, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science began to converge. In 1980, Paul Benioff introduced the quantum Turing machine, which uses quantum theory to describe a simplified computer.[8] When digital computers became faster, physicists faced an exponential increase in overhead when simulating quantum dynamics,[9] prompting Yuri Manin and Richard Feynman to independently suggest that hardware based on quantum phenomena might be more efficient for computer simulation.[10][11][12] In a 1984 paper, Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard applied quantum theory to cryptography protocols and demonstrated that quantum key distribution could enhance information security.[13][14]

Peter Shor (pictured here in 2017) showed in 1994 that a scalable quantum computer would be able to break RSA encryption.

Peter Shor (pictured here in 2017) showed in 1994 that a scalable quantum computer would be able to break RSA encryption.

Quantum algorithms then emerged for solving oracle problems, such as Deutsch's algorithm in 1985,[15] the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm in 1993,[16] and Simon's algorithm in 1994.[17] These algorithms did not solve practical problems, but demonstrated mathematically that one could gain more information by querying a black box with a quantum state in superposition, sometimes referred to as quantum parallelism.[18] Peter Shor built on these results with his 1994 algorithms for breaking the widely used RSA and Diffie–Hellman encryption protocols,[19] which drew significant attention to the field of quantum computing.[20] In 1996, Grover's algorithm established a quantum speedup for the widely applicable unstructured search problem.[21][22] The same year, Seth Lloyd proved that quantum computers could simulate quantum systems without the exponential overhead present in classical simulations,[23] validating Feynman's 1982 conjecture.[24]

Over the years, experimentalists have constructed small-scale quantum computers using trapped ions and superconductors.[25] In 1998, a two-qubit quantum computer demonstrated the feasibility of the technology,[26][27] and subsequent experiments have increased the number of qubits and reduced error rates.[25] In 2019, Google AI and NASA announced that they had achieved quantum supremacy with a 54-qubit machine, performing a computation that is impossible for any classical computer.[28][29][30] However, the validity of this claim is still being actively researched.[31][32]

The threshold theorem shows how increasing the number of qubits can mitigate errors,[33] yet fully fault-tolerant quantum computing remains "a rather distant dream".[34] According to some researchers, noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) machines may have specialized uses in the near future, but noise in quantum gates limits their reliability.[34]

Investment in quantum computing research has increased in the public and private sectors.[35][36] As one consulting firm summarized,[37]

... investment dollars are pouring in, and quantum-computing start-ups are proliferating. ... While quantum computing promises to help businesses solve problems that are beyond the reach and speed of conventional high-performance computers, use cases are largely experimental and hypothetical at this early stage.

Quantum information processing[edit]

See also: Introduction to quantum mechanics

Computer engineers typically describe a modern computer's operation in terms of classical electrodynamics. Within these "classical" computers, some components (such as semiconductors and random number generators) may rely on quantum behavior, but these components are not isolated from their environment, so any quantum information quickly decoheres. While programmers may depend on probability theory when designing a randomized algorithm, quantum mechanical notions like superposition and interference are largely irrelevant for program analysis.

Quantum programs, in contrast, rely on precise control of coherent quantum systems. Physicists describe these systems mathematically using linear algebra. Complex numbers model probability amplitudes, vectors model quantum states, and matrices model the operations that can be performed on these states. Programming a quantum computer is then a matter of composing operations in such a way that the resulting program computes a useful result in theory and is implementable in practice.

The prevailing model of quantum computation describes the computation in terms of a network of quantum logic gates.[38] This model is a complex linear-algebraic generalization of boolean circuits.[a]

Quantum information[edit]

The qubit serves as the basic unit of quantum information. It represents a two-state system, just like a classical bit, except that it can exist in a superposition of its two states. In one sense, a superposition is like a probability distribution over the two values. However, a quantum computation can be influenced by both values at once, inexplicable by either state individually. In this sense, a "superposed" qubit stores both values simultaneously.

A two-dimensional vector mathematically represents a qubit state. Physicists typically use Dirac notation for quantum mechanical linear algebra, writing |ψ⟩ 'ket psi' for a vector labeled ψ. Because a qubit is a two-state system, any qubit state takes the form α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where |0⟩ and |1⟩ are the standard basis states,[b] and α and β are the probability amplitudes. If either α or β is zero, the qubit is effectively a classical bit; when both are nonzero, the qubit is in superposition. Such a quantum state vector acts similarly to a (classical) probability vector, with one key difference: unlike probabilities, probability amplitudes are not necessarily positive numbers. Negative amplitudes allow for destructive wave interference.[c]

When a qubit is measured in the standard basis, the result is a classical bit. The Born rule describes the norm-squared correspondence between amplitudes and probabilities—when measuring a qubit α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, the state collapses to |0⟩ with probability |α|2, or to |1⟩ with probability |β|2. Any valid qubit state has coefficients α and β such that |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. As an example, measuring the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩ would produce either |0⟩ or |1⟩ with equal probability.

Each additional qubit doubles the dimension of the state space. As an example, the vector 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|01⟩ represents a two-qubit state, a tensor product of the qubit |0⟩ with the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩. This vector inhabits a four-dimensional vector space spanned by the basis vectors |00⟩, |01⟩, |10⟩, and |11⟩. The Bell state 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|11⟩ is impossible to decompose into the tensor product of two individual qubits—the two qubits are entangled because their probability amplitudes are correlated. In general, the vector space for an n-qubit system is 2n-dimensional, and this makes it challenging for a classical computer to simulate a quantum one: representing a 100-qubit system requires storing 2100 classical values.

Unitary operators[edit]

See also: Unitarity (physics)

The state of this one-qubit quantum memory can be manipulated by applying quantum logic gates, analogous to how classical memory can be manipulated with classical logic gates. One important gate for both classical and quantum computation is the NOT gate, which can be represented by a matrix

�:=(0110).

�|0⟩=|1⟩

The mathematics of single qubit gates can be extended to operate on multi-qubit quantum memories in two important ways. One way is simply to select a qubit and apply that gate to the target qubit while leaving the remainder of the memory unaffected. Another way is to apply the gate to its target only if another part of the memory is in a desired state. These two choices can be illustrated using another example. The possible states of a two-qubit quantum memory are

|00⟩:=(1000);|01⟩:=(0100);|10⟩:=(0010);|11⟩:=(0001).

In summary, a quantum computation can be described as a network of quantum logic gates and measurements. However, any measurement can be deferred to the end of quantum computation, though this deferment may come at a computational cost, so most quantum circuits depict a network consisting only of quantum logic gates and no measurements.

Copyright © 2026 Jasfar - All Rights Reserved.

FONDED BY MR Sunny Faridi

Announcement

Early we started the progress of desire and motive is you are the way of light or key of wisdom make your path clear move with plan of dreams work with future play with real present learn with past power is yours to decide

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.